Exhibition: June 15th – August 11th, 2017

Opening Reception: Thursday, June 15th, 6-8PM

“Many artists have felt the lure of juxtaposing photographs and text, but few have succeeded as well as Teju Cole. He approaches this problem with an understanding of the limitations and glories of each medium.”—Stephen Shore

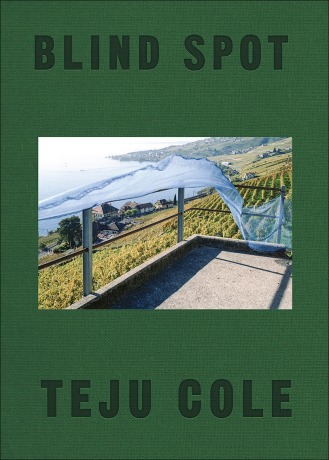

Steven Kasher Gallery is pleased to present the first solo exhibition in New York of acclaimed photographer, essayist and novelist Teju Cole. The exhibition accompanies the publication of Cole’s fourth volume, Blind Spot (Random House, 2017) with a foreword by Siri Hustvedt.

The exhibition features over 30 color photographs from the series Blind Spot, each accompanied by Cole’s lyrical and evocative prose. Viewed together, these works form a multimedia diary of years of near-constant travel. In these photographs, we see what Cole has seen, from a park in Berlin to a mountain range in Switzerland, a church exterior in Lagos to a parking lot in Brooklyn; and we are drawn into the texts—which function as voiceovers—with which Cole complicates his already enigmatic images. At stake here is the question of vision, an exploration Cole began following a temporary spell of blindness in 2011, and which he presents here in a photographic sequence of novelistic intensity.

The exhibition also presents Black Paper, a visceral photographic response to Cole’s experiences following the election of November 2016. This continuously evolving, large-scale work explores buried feelings, haunted space, and all that can be seen through darkness.

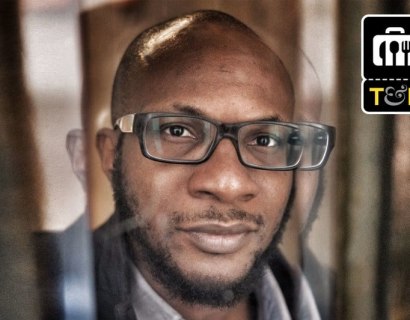

Teju Cole (b. 1975, Nigeria) is a writer, art historian, and photographer. He is the photography critic of the New York Times Magazine and Distinguished Writer in Residence at Bard College. He is the author of three previous books. His novella, Every Day is for the Thief (2014), was named a book of the year by the New York Times, the Globe and Mail, NPR, and the Telegraph and shortlisted for the PEN/Open Book Award. His novel, Open City (2011) won the PEN/Hemingway Award, the New York City Book Award for Fiction, the Rosenthal Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Internationaler Literaturpreis. Open City was also shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award, the New York Public Library Young Lions Award, and the Ondaatje Prize of the Royal Society of Literature. His essay collection, Known and Strange Things (2016), the core of which is his photography essays, was published to rave reviews in the New York Times and the New York Review of Books, among others; named a book of the year by the Guardian, the Financial Times, Time Magazine, and many others; and is the only book to have been shortlisted for two PEN Awards in the same year: the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay and the PEN/Jean Stein Award for originality, merit, and impact.

Cole’s photography has been exhibited in India, Iceland, and the US, published widely, and was the subject of a solo exhibition in Italy in the spring of 2016. His photography column at the New York Times Magazine was a finalist for a 2016 National Magazine Award. He is a recipient of a US Artists award, and received the 2015 Windham Campbell Prize for Fiction.

Teju Cole: Blind Spot and Black Paper will be on view June 15 – August 11, 2017. Steven Kasher Gallery is located at 515 W. 26th St., New York, NY 10001. Gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10 AM to 6 PM. For press and all other inquiries, please contact Cassandra Johnson, 212 966 3978, cassandra@stevenkasher.com.